Big Data

What are big data?

“Big data” are also data, but involve far larger amounts of data than can usually be handled on a desktop computer or in a traditional database. Big data are not only huge in volume, but they grow exponentially with time. Big data are so large and complex that none of the traditional data-management tools are able to store them or process them efficiently. If you have an amount of data that you can process on your computer or the database on your usual server without it crashing, “big data” are likely not what you are working with.

How does big data work?

The field of big data has evolved as technology’s ability to constantly capture information has skyrocketed. Big data are usually captured without being entered into a database by a human being, in real time: in other words, big data are “passively” captured by digital devices.

The internet provides infinite opportunities to gather information, ranging from so-called meta-information or metadata (geographic location, IP address, time, etc.) to more detailed information about users’ behaviors. This is often from online social media or credit card-purchasing behavior. Cookies are one of the principal ways that web browsers gather information about users: they are essentially tiny pieces of data stored on a web browser, or little bits of memory about something you did on a website. (For more on cookies, visit this resource).

Data sets can also be assembled from the Internet of Things, which involves sensors tied to other devices and networks. For example, censor-equipped streetlights might collect traffic information that can then be analyzed to optimize traffic flow. The collection of data through sensors is a common element of smart city infrastructure.

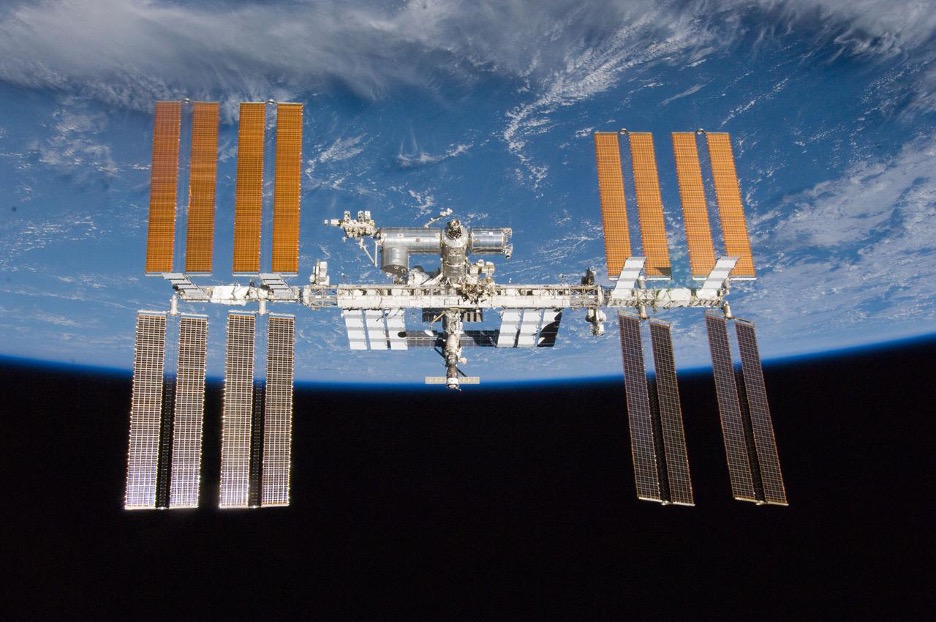

Big data can also be medical or scientific data, such as DNA information or data related to disease outbreaks. This can be useful to humanitarian and development organizations. For example, during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa between 2014 and 2016, UNICEF combined data from a number of sources, including population estimates, information on air travel, estimates of regional mobility from mobile phone records and tagged social media locations, temperature data, and case data from WHO reports to better understand the disease and predict future outbreaks.

Big data are created and used by a variety of actors. In data-driven societies, most actors (private sector, governments, and other organizations) are encouraged to collect and analyze data to notice patterns and trends, measure success or failure, optimize their processes for efficiency, etc. Not all actors will create datasets themselves, often they will collect publicly available data or even purchase data from specialized companies. For instance, in the advertising industry, Data Brokers specialize in collecting and processing information about internet users, which they then sell to advertisers. Other actors will create their own datasets, like energy providers, railway companies, ride-sharing companies, and governments. Data are everywhere, and the actors capable of collecting them intelligently and analyzing them are numerous.

How is big data relevant in civic space and for democracy?

From forecasting presidential elections to helping small-scale farmers deal with changing climate to predicting disease outbreaks, analysts are finding ways to turn Big Data into an invaluable resource for planning and decision-making. Big data are capable of providing civil society with powerful insights and the ability to share vital information. Big data tools have been deployed recently in civic space in a number of interesting ways, for example, to:

- monitor elections and support open government (starting in Kenya with Ushahidi in 2008)

- track epidemics like Ebola in Sierra Leone and other West African nations

- track conflict-related deaths worldwide

- understand the impact of ID systems on refugees in Italy

- measure and predict agricultural success and distribution in Latin America

- press forward with new discoveries in genetics and cancer treatment

- make use of geographic information systems (GIS mapping applications) in a range of contexts, including planning urban growth and traffic flow sustainably, as has been done by the World Bank in various countries in South Asia, East Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean

The use of big data that are collected, processed, and analyzed to improve health systems or environmental sustainability, for example, can ultimately greatly benefit individuals and society. However, a number of concerns and cautions have been raised about the use of big datasets. Privacy and security concerns are foremost, as big data are often captured without our awareness and used in ways to which we may not have consented, sometimes sold many times through a chain of different companies we never interacted with, exposing data to security risks such as data breaches. It is crucial to consider that anonymous data can still be used to “re-identify” people represented in the dataset – achieving 85% accuracy using as little as postal code, gender, and date of birth – conceivably putting them at risk (see discussion of “re-identification” below).

There are also power imbalances (divides) in who is represented in the data as opposed to who has the power to use them. Those who are able to extract value from big data are often large companies or other actors with the financial means and capacity to collect (sometimes purchase), analyze, and understand the data.

This means the individuals and groups whose information is put into datasets (shoppers whose credit card data is processed, internet users whose clicks are registered on a website) do not generally benefit from the data they have given. For example, data about what items shoppers buy in a store is more likely used to maximize profits than to help customers with their buying decisions. The extractive way that data are taken from individuals’ behaviors and used for profit has been called “surveillance capitalism“, which some believe is undermining personal autonomy and eroding democracy.

The quality of datasets must also be taken into consideration, as those using the data may not know how or where they were gathered, processed, or integrated with other data. And when storing and transmitting big data, security concerns are multiplied by the increased numbers of machines, services, and partners involved. It is also important to keep in mind that big datasets themselves are not inherently useful, but they become useful along with the ability to analyze them and draw insights from them, using advanced algorithms, statistical models, etc.

Last but not least, there are important considerations related to protecting the fundamental rights of those whose information appears in datasets. Sensitive, personally identifiable, or potentially personally identifiable information can be used by other parties or for other purposes than those intended, to the detriment of the individuals involved. This is explored below and in the Risks section, as well as in other primers.

Protecting anonymity of those in the datasetAnyone who has done research in the social or medical sciences should be familiar with the idea that when collecting data on human subjects, it is important to protect their identities so that they do not face negative consequences from being involved in research, such as being known to have a particular disease, voted in a particular way, engaged in stigmatized behavior, etc. (See the Data Protection resource). The traditional ways of protecting identities – removing certain identifying information, or only reporting statistics in aggregate – can and should also be used when handling big datasets to help protect those in the dataset. Data can also be hidden in multiple ways to protect privacy: methods include encryption (encoding), tokenization, and data masking. Talend identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the primary strategies for hiding data using these methods.

One of the biggest dangers involved in using big datasets is the possibility of re-identification: figuring out the real identities of individuals in the dataset, even if their personal information has been hidden or removed. To give a sense of how easy it could be to identify individuals in a large dataset, one study found that using only three fields of information—postal code, gender, and date of birth—it was possible to identify 87% of Americans individually, and then connect their identities to publicly-available databases containing hospital records. With more data points, researchers have demonstrated a near-perfect ability to identify individuals in a dataset: four random pieces of data credit card records could achieve 90% identifiability, and researchers were able to re-identify individuals with 99.98% accuracy using 15 data points.

Ten simple rules for responsible big data research, quoted from a paper of the same name by Zook, Barocas, Boyd, Crawford, Keller, Gangadharan, et al, 2017

-

Acknowledge that data are people and that data can do harm. Most data represent or affect people. Simply starting with the assumption that all data are people until proven otherwise places the difficulty of disassociating data from specific individuals front and center.

-

Recognize that privacy is more than a binary value. Privacy may be more or less important to individuals as they move through different contexts and situations. Looking at someone’s data in bulk may have different implications for their privacy than looking at one record. Privacy may be important to groups of people (say, by demographic) as well as to individuals.

-

Guard against the reidentification of your data. Be aware that apparently harmless, unexpected data, like phone battery usage, could be used to re-identify data. Plan to ensure your data sharing and reporting lowers the risk that individuals could be identified.

-

Practice ethical data sharing. There may be times when participants in your dataset expect you to share (such as with other medical researchers working on a cure), and others where they trust you not to share their data. Be aware that other identifying data about your participants may be gathered, sold, or shared about them elsewhere, and that combining that data with yours could identify participants individually. Be clear about how and when you will share data and stay responsible for protecting the privacy of the people whose data you collect.

-

Consider the strengths and limitations of your data; big does not automatically mean better. Understand where your large dataset comes from, and how that may evolve over time. Don’t overstate your findings and acknowledge when they may be messy or have multiple meanings.

-

Debate the tough, ethical choices. Talk with your colleagues about these ethical concerns. Follow the work of professional organizations to stay current with concerns.

-

Develop a code of conduct for your organization, research community, or industry and engage your peers in creating it to ensure unexpected or under-represented perspectives are included.

-

Design your data and systems for auditability. This both strengthens the quality of your research and services and can give early warnings about problematic uses of the data.

-

Engage with the broader consequences of data and analysis practices. Keep social equality, the environmental impact of big data processing, and other society-wide impacts in view as you plan big data collection.

-

Know when to break these rules. With debate, code of conduct, and auditability as your guide, consider that in a public health emergency or other disaster, you may find there are reasons to put the other rules aside.

Those providing their data may not be aware at the time that their data may be sold later to data brokers who may then re-sell them.

Unfortunately, data privacy consent forms are generally hard for the average person to read, even in the wake of General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR ) expansion of privacy protections. Terms of Service (ToS documents) are so notoriously difficult to read that one filmmaker even made a documentary on the subject. Researchers who have studied terms of service and privacy policies have found that users generally accept them without reading them because they are too long and complex. Otherwise, users that need to access a platform or service for personal reasons (for example to get in contact with a relative) or for their livelihood (to deliver their products to customers) may not be able to simply reject the ToS when they have no viable or immediate alternative.

Important work is being done to try to protect users of platforms and services from these kinds of abusive data-sharing situations. For example, Carnegie Mellon’s Usable Privacy and Security laboratory (CUPS) has developed best practices to inform users about how their data may be used. These take the shape of data privacy “nutrition labels” that are similar to FDA-specified food nutrition labels and are evidence-based.

Opportunities

Big data can have positive impacts when used to further democracy, human rights, and governance issues. Read below to learn how to more effectively and safely think about big data in your work.

Greater insightBig datasets can present some of the richest, most comprehensive information that has ever been available in human history. Researchers using big datasets have access to information from a massive population. These insights can be much more useful and convenient than self-reported data or data gathered from logistically tricky observational studies. One major trade-off is between the richness of the insights gained through self-reported or very carefully collected data, versus the ability to generalize the insights from big data. Big data gathered from social-media activity or sensors also can allow for the real-time measurements of activity at a large scale. Big data insights are very important in the field of logistics. For example, the United States Postal Service collects data from across its package deliveries using GPS and vast networks of sensors and other tracking methods, and they then process these data with specialized algorithms. These insights allow them to optimize their deliveries for environmental sustainability.

Making big datasets publicly available can begin to take steps toward closing divides in access to data. Apart from some public datasets, big data often ends up as the property of corporations, universities, and other large organizations. Even though the data produced are about individual people and their communities, those individuals and communities may not have the money or technical skills needed to access those data and make productive use of them. This creates the risk of worsening existing digital divides.

Publicly available data have helped communities understand and act on government corruption, municipal issues, human-rights abuses, and health crises, among other things. Though again, when data are made public, they are of particular importance to ensure strong privacy for those whose data is in the dataset. The work of the Our Data Bodies project provides additional guidance for how to engage with communities whose data is in the datasets. Their workshop materials can support community understanding and engagement in making ethical decisions around data collection and processing, and about how to monitor and audit data practices.

Risks

The use of emerging technologies to collect data can also create risks in civil society programming. Read below on how to discern the possible dangers associated with big data collection and use in DRG work, as well as how to mitigate for unintended – and intended – consequences.

SurveillanceWith the potential for re-identification as well as the nature and aims of some uses of big data, there is a risk that individuals included in a dataset will be subjected to surveillance by governments, law enforcement, or corporations. This may put the fundamental rights and safety of those in the dataset at risk.

The Chinese government is routinely criticized for the invasive surveillance of Chinese citizens through gathering and processing big data. More specifically, the Chinese government has been criticized for their system of social ranking of citizens based on their social media, purchasing, and education data, as well as the gathering of DNA of members of the Uighur minority (with the assistance of a US company, it should be noted). China is certainly not the only government to abuse citizen data in this way. Edward Snowden’s revelations about the US National Security Agency’s gathering and use of social media and other data were among the first public warnings about the surveillance potential of big data. Concerns have also been raised about partnerships involved in the development of India’s Aadhar biometric ID system, a technology whose producers are eager to sell it to other countries. In the United States, privacy advocates have raised concerns about companies and governments gathering data at scale about students by using their school-provided devices, a concern that should also be raised in any international context when laptops or mobiles are provided for students.

It must be emphasized that surveillance concerns are not limited to the institutions originally gathering the data, whether governments or corporations. When data are sold or combined with other datasets, it is possible that other actors, from email scammers to abusive domestic partners, could access the data and track, exploit, or otherwise harm people appearing in the dataset.

Because big data are collected, cleaned, and combined through long, complex pipelines of software and storage, it presents significant challenges for security. These challenges are multiplied whenever the data are shared between many organizations. Any stream of data arriving in real time (for example, information about people checking into a hospital) will need to be specifically protected from tampering, disruption, or surveillance. Given that data may present significant risks to the privacy and safety of those included in the datasets and may be very valuable to criminals, it is important to ensure sufficient resources are provided for security.

Existing security tools for websites are not enough to cover the entire big data pipeline. Major investments in staff and infrastructure are needed to provide proper security coverage and respond to data breaches. And unfortunately, within the industry, there are known shortages of big data specialists, particularly security personnel familiar with the unique challenges big data presents. Internet of Things sensors present a particular risk if they are part of the data-gathering pipeline; these devices are notorious for having poor security. For example, a malicious actor could easily introduce fake sensors into the network or fill the collection pipeline with garbage data in order to render your data collection useless.

Big data companies and their promoters often make claims that big data can be more objective or accurate than traditionally-gathered data, supposedly because human judgment does not come into play and because the scale at which it is gathered is richer. This picture downplays the fact that algorithms and computer code also bring human judgment to bear on data, including biases and data that may be accidentally excluded. Human interpretation is also always necessary to make sense of patterns in big data; so again, claims of objectivity should be taken with healthy skepticism.

It is important to ask questions about data-gathering methods, algorithms involved in processing, and the assumptions or inferences made by the data gatherers/programmers and their analyses to avoid falling into the trap of assuming big data are “better.” For example, while data about the proximity of two cell phones tells you the fact that two people were near each other, only human interpretation can tell you why those two people were near each other. How an analyst interprets that closeness may differ from what the people carrying the cell phones might tell you. For example, this is a major challenge in using phones for “contact tracing” in epidemiology. During the COVID-19 health crisis, many countries raced to build contact tracing cellphone apps. The precise purposes and functioning of these apps varies widely (as has their effectiveness) but it is worth noting that major tech companies have preferred to refer to these apps as “exposure-risk notification” apps rather than contact tracing: this is because the apps can only tell you if you have been in proximity with someone with the coronavirus, not whether or not you have contacted the virus.

As with all data, there are pitfalls when it comes to interpreting and drawing conclusions. Because big data is often captured and analyzed in real-time, it may be particularly weak in providing historical context for the current patterns it is highlighting. Anyone analyzing big data should also consider what its source or sources were, whether the data was combined with other datasets, and how it was cleaned. Cleaning refers to the process of correcting or removing inaccurate or extraneous data. This is particularly important with social-media data, which can have lots of “noise” (extra information) and are therefore almost always cleaned.

Questions

If you are trying to understand the implications of big data in your work environment, or are considering using aspects of big data as part of your DRG programming, ask yourself these questions:

- Is gathering big data the right approach for the question you’re trying to answer? How would your question be answered differently using interviews, historical research, or a focus on statistical significance?

- Do you already have these data, or are they publicly available? Is it really necessary to acquire these data yourself?

- What is your plan to make it impossible to identify individuals through their data in your dataset? If the data come from someone else, what kind of de-anonymization have they already performed?

- How could individuals be made more identifiable by someone else when you publish your data and findings? What steps can you take to lower the risk they will be identified?

- What is your plan for getting consent from those whose data you are collecting? How will you make sure your consent document is easy for them to understand?

- If your data come from another organization, how did they seek consent? Did that consent include consent for other organizations to use the data?

- If you are getting data from another organization, what is the original source of these data? Who collected them, and what were they trying to accomplish?

- What do you know about the quality of these data? Is someone inspecting them for errors, and if so, how? Did the collection tools fail at any point, or do you suspect that there might be some inaccuracies or mistakes?

- Have these data been integrated with other datasets? If data were used to fill in gaps, how was that accomplished?

- What is the end-to-end security plan for the data you are capturing or using? Are there third parties involved whose security propositions you need to understand?

Case Studies

Big Data for climate-smart agriculture

“Scientists at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) have applied Big Data tools to pinpoint strategies that work for small-scale farmers in a changing climate…. Researchers have applied Big Data analytics to agricultural and weather records in Colombia, revealing how climate variation impacts rice yields. These analyses identify the most productive rice varieties and planting times for specific sites and seasonal forecasts. The recommendations could potentially boost yields by 1 to 3 tons per hectare. The tools work wherever data is available, and are now being scaled out through Colombia, Argentina, Nicaragua, Peru and Uruguay.”

School-Issued Devices and Student Privacy, particularly the Best Practices for Ed Tech Companies section.

“Students are using technology in the classroom at an unprecedented rate…. Student laptops and educational services are often available for a steeply reduced price and are sometimes even free. However, they come with real costs and unresolved ethical questions. Throughout EFF’s investigation over the past two years, [they] have found that educational technology services often collect far more information on kids than is necessary and store this information indefinitely. This privacy-implicating information goes beyond personally identifying information (PII) like name and date of birth, and can include browsing history, search terms, location data, contact lists, and behavioral information…All of this often happens without the awareness or consent of students and their families.”

This paper includes case studies of big data used to track changes in urbanization, traffic congestion, and crime in cities. “[I]nnovative applications of geospatial and sensing technologies and the penetration of mobile phone technology are providing unprecedented data collection. This data can be analyzed for many purposes, including tracking population and mobility, private sector investment, and transparency in federal and local government.”

Battling Ebola in Sierra Leone: Data Sharing to Improve Crisis Response.

“Data and information have important roles to play in the battle not just against Ebola, but more generally against a variety of natural and man-made crises. However, in order to maximize that potential, it is essential to foster the supply side of open data initiatives – i.e., to ensure the availability of sufficient, high-quality information. This can be especially challenging when there is no clear policy backing to push actors into compliance and to set clear standards for data quality and format. Particularly during a crisis, the early stages of open data efforts can be chaotic, and at times redundant. Improving coordination between multiple actors working toward similar ends – though difficult during a time of crisis – could help reduce redundancy and lead to efforts that are greater than the sum of their parts.”

Tracking Conflict-Related Deaths: A Preliminary Overview of Monitoring Systems.

“In the framework of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, states have pledged to track the number of people who are killed in armed conflict and to disaggregate the data by sex, age, and cause—as per Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Indicator 16. However, there is no international consensus on definitions, methods, or standards to be used in generating the data. Moreover, monitoring systems run by international organizations and civil society differ in terms of their thematic coverage, geographical focus, and level of disaggregation.”

Balancing data utility and confidentiality in the US census.

Describes how the Census is using differential privacy to protect the data of respondents. “As the Census Bureau prepares to enumerate the population of the United States in 2020, the bureau’s leadership has announced that they will make significant changes to the statistical tables the bureau intends to publish. Because of advances in computer science and the widespread availability of commercial data, the techniques that the bureau has historically used to protect the confidentiality of individual data points can no longer withstand new approaches for reconstructing and reidentifying confidential data. … [R]esearch at the Census Bureau has shown that it is now possible to reconstruct information about and reidentify a sizeable number of people from publicly available statistical tables. The old data privacy protections simply don’t work anymore. As such, Census Bureau leadership has accepted that they cannot continue with their current approach and wait until 2030 to make changes; they have decided to invest in a new approach to guaranteeing privacy that will significantly transform how the Census Bureau produces statistics.”

References

Find below the works cited in this resource.

- Andrejevic, Mark, (2014). The Big Data Divide. International Journal of Communication 8, pp. 1673–1689.

- Bhatt, Vikas, (2020). The Significance of Data Cleansing In Big Data. Aithority.

- Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), (2015). Big data for climate-smart agriculture. CGIAR/CCAFS.

- Cylab Usable Privacy and Security Laboratory (CUPS), (n.d.). Privacy Nutrition Labels. Carnegie Mellon University.

- Gebhart, Gennie, (2017). Spying on Students: School-Issued Devices and Student Privacy. Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF).

- Gellman, Barton, (2020). Inside the NSA’s Secret Tool for Mapping Your Social Network. Wired.

- Grauer, Yael, (2018). What Are ‘Data Brokers,’ and Why Are They Scooping Up Information About You?

- Hvistendahl, Mara, (2017). Inside China’s Vast New Experiment in Social Ranking. Wired.

- Laidler, John, (2019). High tech is watching you. The Harvard Gazette.

- Lomas, Natasha, (2019). Researchers spotlight the lie of ‘anonymous’ data. Tech Crunch.

- Montjoye, Yves-Alexandre, et al., (2015). Unique in the shopping mall: On the reidentifiability of credit card metadata. Science 347(6221), pp. 536-539.

- Panday, Jyoti, (2018). Can India’s Biometric Identity Program Aadhaar Be Fixed? Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF).

- Sweeney, Latanya, (2002). k-Anonymity: A model for protecting privacy. International Journal on Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-based Systems, 10 (.5)

- Talend, (n.d.). What is Data Obfuscation?

- The World Bank. (2017). Big data and thriving cities.

- Wlosik, Michal & Michael Sweeney, (n.d.). What’s the Difference Between First-Party and Third-Party Cookies?

- Zook, Matthew, et al., (2017).Ten simple rules for responsible big data research. PLOS Computational Biology.

Additional Resources

- Barocas, Solon et al. (2014). Data and civil rights technology primer. Data & Society.

- Berman, Gabrielle et al. (2018). Ethical considerations when using geospatial technologies for evidence generation. UNICEF: Geospatial technologies have transformed the way we visualize and understand social phenomena and physical environments. This paper examines the benefits, risks and ethical considerations when undertaking evidence generation using geospatial technologies.

- Boyd, Danah & Kate Crawford. (2011). Six Provocations for Big Data.

- Boyd, Danah, Keller, Emily F. & Bonnie Tijerina. (2016). Supporting Ethical Data Research: An Exploratory Study of Emerging Issues in Big Data and Technical Research. Data & Society: includes discussion of informed consent and secure data storage.

- Cranor, Lorrie. (2012). Necessary But Not Sufficient: Standardized Mechanisms for Privacy Notice and Choice: This study provides an overview of the problems with existing privacy policies as they are presented to users, reviews the idea behind notice, choice, and user empowerment as privacy protection mechanisms, and suggests directions for improvement.

- Cyphers, Bennett & Gennie Gebhart. (2019). Behind the One-Way Mirror: A Deep Dive into the Technology of Corporate Surveillance. EFF: background on how corporations collect our data, combine it with other datasets, and sell it to each other.

- Data and Society’s “primers” on data and civil rights in different topic areas: Consumer finance, Criminal justice, Education, Employment, Health and Housing.

- Data Privacy Project: includes resources to support librarians, educators, and community members in understanding how their data is used and transferred.

- Garfinkle, Simson. (2015). NIST guidance on de-identification of personal information.

- Garfinkle, Simson. (2016). NIST guidance on de-identifying government data sets.

- Global Health Sites Mapping Project: Health Sites is an initiative to build an open data commons of health facility data with OpenStreetMap.

- GSM Association. (2014). GSMA guidelines on the protection of privacy in the use of mobile phone data for responding to the Ebola outbreak: This document outlines, in broad terms, the privacy standards that mobile operators will apply when subscriber mobile-phone data are used, in these exceptional circumstances, for responses to the Ebola outbreak.

- Humanitarian Data Exchange: Find, share, and use humanitarian data all in one place, powered by UNOCHA.

- Humanitarian Tracker’s reports on using large datasets to track human rights abuses and map crises.

- Marr, Bernard. (2015). A brief history of data. World Economic Forum.

- Metcalf, Jacob. (2016). Big Data Analytics and Revision of the Common Rule. Communications of the Association for Computing Machinery 59(7): contains guidance on the evolution of ethical standards for research on human subjects in light of concerns about big data.

- (2013). Public bodies regularly releasing personal information by accident in Excel files. mySociety: When officers within public bodies release FOI information that they think they have anonymized, they import personally identifiable information and an attempt is made to summarize it in anonymous form, often using pivot tables or charts.

- Nugroho, Rininita Putri et al. (2015). A comparison of national open data policies: Lessons learned. Transforming Government, 9(3): provides a comprehensive cross-national comparative framework to compare open data policies from different countries and to derive lessons for developing open data policies.

- Onuoha, Mimi. (2017). What it takes to truly delete data. FiveThirtyEight.

- Open Data Institute. (2018). Guide to Open Data Standards: Open standards for data are reusable agreements that make it easier for people and organizations to publish, access, share and use better quality data. This guidebook helps people and organizations create, develop, and adopt open standards for data.

- Our Data Bodies: project which includes materials and activities for talking with communities about how their data is used and case studies of their work.

- Responsible Data Project: a community forum “for those who use data in social change and advocacy to develop practical approaches to addressing the ethical, legal, social and privacy-related challenges they face. [They] identify the unintended consequences of using data in this kind of work, and bring people together to create solutions.” The project provides a list of resources for those seeking to make responsible use of big data and has a mailing list.

- Technology Association of Grantmakers. (2019). Cybersecurity Essentials for Philanthropy Series: aims to reduce your organization’s risk with practices and suggestions shared from philanthropic organizations throughout North America.

- The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Who Has Your Face: tool which keeps track of American governmental organizations that have photos of faces.

- UN Global Pulse: the UN’s big data organization.

- (2019). Center for Humanitarian Data – Data Responsibility Guidelines: offer a set of principles, processes and tools that support the safe, ethical and effective management of data in humanitarian response.

- (2019). Guidance Note: Data Incident Management: Without a shared language and clear approach to data incident management, humanitarian organizations risk exacerbating existing vulnerabilities as well as creating new ones, which can lead to adverse effects for affected people and aid workers. This Guidance Note helps address these gaps in understanding and practice.

- (2019). Guidance Note: Statistical Disclosure Control: Along with an overview of what SDC is and what tools are available, the Guidance Note outlines how the Centre is using this process to mitigate risk for datasets shared on HDX (UN OCHA’s open platform, Humanitarian Data Exchange).

- Ur, Blase & Yang Wang. (2013). A Cross-Cultural Framework for Protecting User Privacy in Online Social Media.

- Usable Privacy Project: a partnership between Carnegie Mellon and other universities that has good information on supporting users’ informed consent, including guidelines for exemplary privacy policy presentations, data privacy “nutrition labels,” and a video summarizing the problems with existing privacy policies.

- (2019). Considerations for Using Data Responsibly: provides USAID staff and local partners with a framework for identifying and understanding risks associated with development data. USAID’s Journey to Self-Reliance includes supporting countries to build their own technological capacity and readiness by taking ownership of their data and being held accountable that it is kept safe.

- Ushahidi’s blog posts, specifically those on big data.

- Ward, Amy, Sample, Forster, Chantal & Karen Graham. (2019). Funder’s Guide: Supporting Cybersecurity with Non-Profit Partners and Grantees: This guide answers two questions: How can foundations better support cybersecurity among nonprofits and grantees? And what is the responsibility of grant makers for cybersecurity in the sector?