Blockchain

What is Blockchain?

A blockchain is a distributed database existing on multiple computers at the same time, with a detailed and un-changeable transaction history leveraging cryptography. Blockchain-based technologies, perhaps most famous for their use in “cryptocurrencies ” such as Bitcoin, are also referred to as “distributed ledger technology (DLT).”

How does Blockchain work?

Blockchain is a constantly growing database as new sets of recordings, or ‘blocks,’ are added to it. Each block contains a timestamp and a link to the previous block, so they form a chain. The resulting blockchain is not managed by any particular body; instead, everyone in the network has access to the whole database. Old blocks are preserved forever, and new blocks are added to the ledger irreversibly, making it impossible to erase or manipulate the database records.

Blockchain can provide solutions for very specific problems. The most clear-cut use case is for public, shared data where all changes or additions need to be clearly tracked, and where no data will ever need to be redacted. Different uses require different inputs (computing power, bandwidth, centralized management), which need to be carefully considered based on each context. Blockchain is also an over-hyped concept applied to a range of different problems where it may not be the most appropriate technology, or in some cases, even a responsible technology to use.

There are two core concepts around Blockchain technology: the transaction history aspect and the distributed aspect. They are technically tightly interwoven, but it is worth considering them and understanding them independently as well.

'Immutable' Transaction HistoryImagine stacking blocks. With increasing effort, one can continue adding more blocks to the tower, but once a block is in the stack, it cannot be removed without fundamentally and very visibly altering—and in some cases destroying—the tower of blocks. A blockchain is similar in that each “block” contains some amount of information—information that may be used, for example, to track currency transactions and store actual data. (You can explore the bitcoin blockchain, which itself has already been used to transmit messages and more, to learn about a real-life example.)

This is a core aspect of the blockchain technology, generally called immutability, meaning data, once stored, cannot be altered. In a practical sense, blockchain is immutable, though a 100% agreement among users could permit changes and actually making those changes would be incredibly tedious.

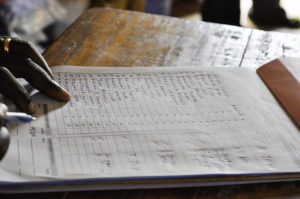

Blockchain is, at its simplest, a valuable digital tool that replicates online the value of a paper-and-ink logbook. While this can be useful to track a variety of sequential transactions or events (ownership of a specific item / parcel of land / supply chain) and could even be theoretically applied to concepts like voting or community ownership and management of resources, it comes with an important caveat. Mistakes can never be truly unmade, and changes to data tracked in a blockchain can never be updated.

Many of the potential applications of blockchain would rely on one of the pieces of data tracked being the identity of a person or legal organization. If that entity changes, their previous identity will be forever immutably tracked and linked to the new identity. On top of being damaging to a person fleeing persecution or legally changing their identity, in the case of transgender individuals, for example, this is also a violation of the right to privacy established under international human rights law.

The second core tenet of blockchain technology is the absence of a central authority or oracle of “truth.” By nature of the unchangeable transaction records, every stakeholder contributing to a blockchain tracks and verifies the data it contains. At scale, this provides powerful protection against problems common not only to NGOs but to the private sector and other fields that are reliant on one service to maintain a consistent data store. This feature can protect a central system from collapsing or being censored, corrupted, lost, or hacked — but at the risk of placing significant hurdles in the development of the protocol and requirements for those interacting with the data.

A common misconception is that blockchain is completely open and transparent. Blockchains may be private, with various forms of permissions applied. In such cases, some users have more control over the data and transactions than others. Privacy settings for blockchain can make for easier management, but also replicate some of the specific challenges that blockchains, in theory, are solving.

Permissionless blockchains are public, so anyone can interact with and participate in them. Permissioned blockchains, on the other hand, are closed networks, which only specific actors can access and contribute to. As such, permissionless blockchains are more transparent and decentralized, while permissioned blockchains are governed by an entity or a group of entities that can customize the platform, choosing who can participate, the level of transparency, and whether or not to use digital assets. Another key difference is that public blockchains tend to be anonymous, while private ones, by nature, cannot be. Because of this, permissioned blockchain is chosen in many human-rights use cases, using identity to hold users accountable.

How is blockchain relevant in civic space and for democracy?

Blockchain technology has the potential to provide substantial benefits in the development sector broadly, as well as specifically for human rights programs. By providing a decentralized, verifiable source of data, blockchain technology can be a more transparent, efficient form of information and data management for improved governance, accountability, financial transparency, and even digital identities. While blockchain can be effective when used strategically on specific problems, practitioners who choose to use it must do so fastidiously. The decisions to use DLTs should be based on a detailed analysis and research on comparable technologies, including non-DLT options. As blockchains are used more and more for governance and in the civic space, irresponsible applications threaten human rights, especially data security and the right to privacy.

By providing a decentralized, verifiable source of data, blockchain technology can enable a more transparent, efficient form of information and data management. Practitioners should understand that blockchain technology can be applied to humanitarian challenges, but it is not a separate humanitarian innovation in itself.

Blockchain for the Humanitarian Sector – Future Opportunities

Blockchains lend themselves to some interesting tools being used by companies, governments, and civil society. Examples of how blockchain technology may be used in civic space include: land titles (necessary for economic mobility and preventing corruption), digital IDs (especially for displaced persons), health records, voucher-based cash transfers, supply chain, censorship resistant publications and applications, digital currency , decentralized data management , recording votes, crowdfunding and smart contracts. Some of these examples are discussed below. Specific examples of the use of blockchain technology may be found on this page under case studies.

Blockchain’s core tenets – an immutable transaction history and its distributed and decentralized nature – lend themselves to some interesting tools being used by companies, governments, and civil society. The risks and opportunities these present will be explored more fully in the relevant sections below, while specific examples will be given in the Case Studies section but, at a high level, many actors are looking at leveraging blockchain in the following ways:

Smart ContractsSmart contracts are agreements that provide automatic payments on the completion of a specific task or event. For example, in civic space, smart contracts could be used to execute agreements between NGOs and local governments to expedite transactions, lower costs, and reduce mutual suspicions. However, since these contracts are “defined” in code, any software bugs can interfere with the intent of the contract or become potential loopholes in which the contract could be exploited. One case of this happened when an attacker exploited a software bug in a smart contract-based firm called The DAO for approximately $50M.

Liquid democracy is a form of democracy wherein, rather than simply voting for elected leaders, citizens also engage in collective decision making. While direct democracy (each individual having a say on every choice a country makes) is not feasible, blockchain could lower the barriers to liquid democracy, a system which would put more power into the hands of the people. Blockchain would allow citizens to register their opinions on specific subject matters or delegate votes to subject matter experts.

Blockchain can be used to tackle governmental corruption and waste in common areas like public procurement. Governments can use blockchain to publicize the steps of procurement processes and build citizen trust as citizens know the transactions recorded cannot have been tampered with. The tool can also be used to automate tax calculation and collection.

Many new cryptocurrencies are considering ways to leverage blockchain for transactions without the volatility of bitcoin, and with other properties, such as speed, cost, stability and anonymity. Cryptocurrencies are also occasionally combined with smart contracts, to establish shared ownership through funding of projects.

In addition, the digital currency subset of blockchain is being used to establish shared ownership (not dissimilar to stocks / shares of large companies) of projects.

The transparency and immutability of blockchain could be used to increase public confidence in elections by integrating electronic voting machines and blockchain. However, there are privacy concerns with publically tracking the tally of votes. Additionally, this system relies on electronic voting machines, which raise some security concerns, as computers can be hacked, and have been met by mistrust in several societies where they were suggested. Online voting through blockchain faces similar distrust, but integrating blockchain into voting would make audits much easier and more reliable. This traceability would also be a useful feature in transparently transmitting results from polling places to tabulation centers.

The decentralized, immutable nature of blockchain provides clear benefits to protecting speech, but not without significant risks. There have been high-visibility uses of blockchain to publish censored speech in China, Turkey, and Catalonia. Article 19 has written an in-depth report specifically on the interplay between freedom of expression and blockchain technologies, which provides a balanced view of the potential benefits and risks and guidance for stakeholders considering engaging in this facet.

Micro-payments through a blockchain can be used to formalize and record actions. This can be useful when carrying out activities with multiple stakeholders where trust, transparency, and a permanent record are valuable, for example, automated auctions (to prevent corruption), voting (to build voter trust), signing contracts (to keep a record of ownership and obligations that will outlast crises that destroy paper or even digital systems), and even for copyright purposes and preventing manipulation of facts.

Ethereum is a cryptocurrency focused on using the blockchain system to help manage decentralized computation and storage through smart contracts and digital payments. Ethereum encourages the development of “distributed apps” which are tied to transactions on the Ethereum Blockchain. Examples of these apps include a X-like tool, and apps that pay for content creation/sharing. See case studies in the cryptocurrencies primer for more detail.

The vast majority of these applications presume some form of micro-payment as part of the transaction. However, this requirement has ramifications for equal access as internet accessibility, capital, and access to online payment systems are all barriers to usage. Furthermore, with funds involved, informed consent is even more essential and challenging to ensure.

Opportunities

Blockchain can have positive impacts when used to further democracy, human rights and governance issues. Read below to learn how to more effectively and safely think about blockchain in your work.

Proof of Digital IntegrityData stored or tracked using blockchain technologies have a clear, sequential, and unalterable chain of verifications. Once data is added to the blockchain, there is ongoing mathematical proof that it has not been altered. This does not provide any assurance that the original data is valid or true, and it means that any data added cannot be deleted or changed – only appended to. However, in civil society, this benefit has been applied to concepts such as creating records for land titles/ownership; improving voting security by ensuring one person matches with one unchangeable vote; and preventing fraud and corruption while enhancing transparency in international philanthropy. It has been used to keep record of digital identities to help people retain ownership over their identity and documents and, in humanitarian contexts, to make voucher-based cash transfers more efficient. As an enabler for digital currency, in some circumstances, blockchain facilitates cross-border funding of civil society. Blockchain could be used not only to preserve identification documents, but qualifications and degrees as well.

A function such as this can provide a solution to the legal invisibility most often borne by refugees and migrants. Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, for example, are often at risk of discrimination and exploitation, because they are stateless. Proponents of blockchain argue that its distributed system can grant individuals with “self-sovereign identity,” a concept by which ownership of identity documents is taken from authorities and put in the hands of individuals. This allows individuals to use their identity documents across a number of authorities while authorities’ access requires a degree of consent. A self-sovereign identity model could be a solution to regulations raised by the GDPR and similar privacy-rights-supporting legislation.

However, if blockchain architects do not secure transaction permissions and public/private state variables, governments could use machine-learning algorithms to monitor public blockchain activity and gain insight into whatever daily, lower- level activities of their citizens are linkable to their blockchain identities. This might include payments (both interpersonal and business) and services, be they health, financial, or other. Anywhere citizens need to show their ID, their location and time would be tracked. While this is an infringement on privacy rights, it is extra problematic for marginalized groups whose legal status in a country can change rapidly and with no warning. Furthermore, such a use of blockchain assumes that individuals would be prepared and able to adopt that technology, an unlikely possibility due to the financial insecurity and lack of access to information and the internet many vulnerable groups, such as refugees, face. In this context, it is impossible to get meaningful informed consent from these target groups.

Blockchain has been used to create transparency in the supply chain and connect consumers directly with the producers of the products they are buying. This enables consumers to know companies are following ethical and sustainable production practices. For example, Moyee Coffee uses blockchain to track their supply chain, and makes this information available to customers, who can confirm the coffee beans were picked by paid, adult farmers and even tip those farmers directly.

Blockchain is resistant to the traditional problems one central authority or data store faces when being attacked or experiencing outages. In a blockchain, data are constantly being shared and verified across all members—although blockchain has been criticized for requiring large amounts of energy, storage, and bandwidth to maintain a shared data store. This decentralization is most valued in digital currencies, which rely on the scale of their blockchain to balance not having a country or region “owning” and regulating the printing of the currency. Blockchain has also been explored to distribute data and coordinate resources without a reliance on a central authority in order to resist censorship.

Blockchain and freedom of expression

Risks

The use of emerging technologies can also create risks in civil society programming. Read below on how to discern the possible dangers associated with blockchain in DRG work, as well as how to mitigate unintended – and intended – consequences.

Unequal AccessThe minimal requirements for an individual or group to engage with Blockchain present a challenge for many. Connectivity, reliable and robust bandwidth, and local storage are all needed. Therefore, mobile phones are often an insufficient device to host or download blockchains. The infrastructure it requires can serve as a barrier to access in areas where Internet connectivity primarily occurs via mobile devices. Because every full node (host of a blockchain) stores a copy of the entire transaction log, blockchains only grow longer and larger with time, and thus can be extremely resource-intensive to download on a mobile device. For instance, over the span of a few years, the blockchains underlying Bitcoin grew from several gigabytes to several hundred. And for a cryptocurrency blockchain, this growth is a necessary sign of healthy economic growth. While the use of blockchain offline is possible, offline components are among the most vulnerable to cyberattacks, and this could put the entire system at risk.

Blockchains — whether they are fully independent or part of existing blockchains — require some percentage of actors to lend processing power to the blockchain, which — especially as they scale — itself becomes either exclusionary or creates classes of privileged users.

Another problem that can undermine the intended benefits of the system is the unequal access to opportunities to convert blockchain-based currencies to traditional currencies. This is especially a problem in relation to philanthropy or to support civil society organizations in restrictive regulatory environments. For cryptocurrencies to have actual value, someone has to be willing to pay money for them.

Beyond these technical challenges, blockchain technology requires a strong baseline understanding of technology and its use in situations where digital literacy itself is a challenge. Use of the technology without a baseline understanding of the consequences is not really consent and could have dire consequences.

There are paths around some of these problems, but any blockchain use needs to reflect on what potential inequalities could be exacerbated by or with this technology.

Further, these technologies are inherently complex, and outside the atypical case where individuals do possess the technical sophistication and means to install blockchain software and set up nodes; the question remains as to how the majority of individuals can effectively access them. This is especially true of individuals who may have added difficulty interfacing with technologies due to disability, literacy, or age. Ill-equipped users are at increased risk of their investments or information being exposed to hacking and theft.

Storing sensitive information on a blockchain – such as biometrics or gender – combined with the immutable aspects of the system, can lead to considerable risks for individuals when this information is accessed by others with the intention to harm. Even when specific personally identifiable information is not stored on a blockchain, pseudonymous accounts are difficult to protect from being mapped to real-world identities, especially if they are connected with financial transactions, services, and/or actual identities. This can erode rights to privacy and protection of personal data, as well as exacerbate the vulnerability of already marginalized populations and persons who change fundamental aspects of their person (gender, name). Data privacy rights, including explicit consent, modification, and deletion of one’s own data are often protected through data protection and privacy legislation, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU that serves as a framework for many other policies around the world. An overview of legislation in this area around the world is kept up to date by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

For example, in September 2017, concerns surfaced about the Bangladeshi government’s plans to create a ‘merged ID’ that would combine citizens’ biometric, financial, and communications data (Rahman, 2017). At that time, some local organizations had started exploring a DLT solution to identify and serve the needs of local Rohingya asylum-seekers and refugees. Because aid agencies are required to comply with national laws, any data recorded on a DLT platform could be subject to automatic data-sharing with government authorities. If these sets of records were to be combined, they would create an indelible, uneditable, untamperable set of records of highly vulnerable Rohingya asylum-seekers, ready for cross-referencing with other datasets. “As development and humanitarian donors and agencies rush to adopt new technologies that facilitate surveillance, they may be creating and supporting systems that pose serious threats to individuals’ human rights.”

These issues raise questions about meaningful, informed consent – how and to what extent do aid recipients understand DLTs and their implications when they receive assistance? […] Most experts agree that data protection needs to be considered not only in the realm of privacy, empowerment and dignity, but also in terms of potential physical impact or harm (ICRC and Brussels Privacy Hub, 2017; ICRC, 2018a)

Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies in the humanitarian sector

As blockchains scale, they require increasing amounts of computational power to stay in sync. In most digital currency blockchains, this scale problem is balanced by rewarding people who contribute to the processing power required with currency. The University of Cambridge estimated in fall 2019 that Bitcoin alone currently uses .28% of global electricity consumption, which, if Bitcoin were a country, would place it as the 41st most energy-consuming country, just ahead of Switzerland. Further, the negative impact is demonstrated by research showing that each Bitcoin transaction takes as much energy as needed to run a well-appointed house and all the appliances in it for an entire week.

As is often the case for emerging technology, the regulations surrounding blockchain are either ambiguous or nonexistent. In some cases, such as when the technology may be used to publish censored speech, regulators overcorrect and block access to the entire system or remove pseudonymous protections of the system in-country. In Western democracies, there are evolving financial regulations as well as concerns around the immutable nature of the records stored in a blockchain. Personally-Identifiable Information (see Privacy, above) in a blockchain cannot be removed or changed as required by the GDPR right to be forgotten, and widely illegal content has already been inserted into the bitcoin blockchain.

While a blockchain has no “central database” which could be hacked, it also has no central authority to adjudicate or resolve problems. A lost or compromised password is almost guaranteed to result in the loss of ability to access funds or worse, digital identities. Compromised passwords or illegitimate use of the blockchain can harm individuals involved, especially when personal information is accessed or when child sexual abuse images are stored forever. Building mechanisms to address this problem undermines the key benefits of the blockchain.

That said, an enormous amount of trust is inherently placed in the software-development process around blockchain technologies, especially those using smart contracts. Any flaw in the software, and any intentional “back door”, could enable an attack that undermines or subverts the entire goal of the project.

Where is trust being placed: whether it is in the coders, the developers, those who design and govern mobile devices or apps; and whether trust is in fact being shifted from social institutions to private actors. All stakeholders should consider what implications does this have and how are these actors accountable to human rights standards.

Questions

If you are trying to understand the implications of blockchain in your work environment, or are considering using aspects of blockchain as part of your DRG programming, ask yourself these questions:

-

Does blockchain provide specific, needed features that existing solutions with proven track records and sustainability do not?

-

Do you really need blockchain, or would a database be sufficient?

-

How will this implementation respect data privacy and control laws such as the GDPR?

-

Do your intended beneficiaries have the internet bandwidth needed to use the product you are developing with blockchain?

-

What external actors/partners will control critical aspects of the tool or infrastructure this project will rely on?

-

What external actors/partners will have access to the data this project creates? What access conditions, limits, or ownership will they have?

-

What level of transparency and trust do you have with these actors/partners?

-

Are there ways to reduce dependency on these actors/partners?

-

How are you conducting and measuring informed consent processes for any data gathered?

-

How will this project mitigate technical, financial, and/or infrastructural inequalities and ensure they are not exacerbated?

-

Will the use of blockchain in your project comply with data protection and privacy laws?

-

Do other existing laws and policies address the risks and offer mitigating measures related to the use of blockchain in your context, such as anti-money-laundering regulation?

-

Are there laws in the works that may mitigate your project or increase costs?

-

Do existing laws enable the benefits you have identified for the blockchain-enabled project?

-

Are these laws aligned with international human rights law, such as the right to privacy, to freedom of expression and opinion, and to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress?

Case Studies

Blockchain and the supply chainBlockchain has been used for supply chain transparency of products that are commonly not ethically sourced. For example, in 2018, the World Wildlife Fund collaborated with Sea Quest Fiji Ltd., a tuna fishing and processing company and ConsenSys, a tech company with an implementer called TraSeable, to use blockchain to trace the origin of tuna caught in a Fijian longline fishery. Each fish was tagged when caught and the entire journey of the fish was recorded on the blockchain. This methodology is a weapon for sustainability and ethical business practices in other supply chains as well, including those that rely on child and forced labor.

A program was developed in Georgia to address corruption in land management in the country. Land ownership is a sector particularly vulnerable to corruption, in part because it is very easy for government officials to extract bribes to register land due to the fact that ownership is recognized through titles, which can easily be lost or destroyed. Blockchain was introduced to provide a transparent and immutable recording of each step of the process to register land, so that the procurement process could be tracked and there would be no danger of losing the record.

After the COVID-19 vaccine was made public, many states considered implementing a vaccine passport system, whereby individuals would be required to show documentation to prove they were vaccinated in order to enter certain countries or buildings. Blockchain was considered as a tool to more easily store vaccine records and track doses without negative consequences for individuals who lose their records. While there are significant data privacy concerns in a system where there is no alternative to allowing one’s data to be stored on a blockchain, this would have significant public health benefits. Furthermore, it demonstrates that future identification documents are likely to rely on blockchain.

Humanitarian aid is the sector where blockchain for human rights and democracy has been adopted the most. Blockchain has been embraced as a way to combat corruption and ensure money and aid reach intended targets, to allow access to donations in countries where crises have affected the banking system, and in coordination with Digital IDs to allow donor organizations to better track funding and get money to people without traditional methods of receiving money.

Sikka, a project of the Nepal Innovation Lab, operates through partnerships with local vendors and cooperatives within the community, sending value vouchers and digital tokens to individuals through SMS. Value vouchers can be used to purchase humanitarian goods from vendors, while digital tokens can be exchanged for cash. The initiative also supplies donors with data for monitoring and evaluation purposes. The International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) has a similar project, the Blockchain Open Loop Cash Transfer Pilot Project for cash transfer programming. The Kenya-based project utilized a mobile money transfer service operating in the country, Safaricom M-Pesa, to send payments to the mobile wallets of beneficiaries without the need for national ID documentation, and blockchain was used to track the payments. A management platform called “Red Rose” allowed donor organizations to manage data, and the program explored many of the ethics concerns around the use of blockchain.

The Start Network is another humanitarian aid organization that has experimented with using blockchain to disperse funds because of the reduced transfer fees, transparency, and speed benefits. Using the Disperse platform, a distribution platform for foreign aid, the Start Network hoped to increase the humanitarian sector’s comfort with introducing new tech solutions.

AIDONIC is a private company with a donation management tool that incentivizes humanitarian donation with a platform allowing donors, even individuals, greater control over what their donations are used for. Small donors can choose specific initiatives, which will launch when fully funded, and throughout projects, donors can monitor, track, and trace their contributions.

A similar humanitarian application of blockchain is collaboration. The World Food Program’s Building Blocks project allows organizations that work in the region but offer different types of humanitarian aid to coordinate their efforts. All of the actions of the humanitarian organizations are recorded on a shared private blockchain. Though the program has a policy to support data privacy, including not recording any data other than that required, pseudonymous data only being released to approved humanitarian orgs, and not recording any sensitive information, humanitarian aid applications of blockchain raise a lot of cybersecurity and data privacy concerns, and all members of the network must be approved. The project has not been as successful as hoped; only UN Women and the World Food Program are full members, but the network makes it easier for beneficiaries to access aid from both organizations, and it provides a clearer picture for aid organizations of what types of aid are being provided and what is missing.

In addition to its applications in humanitarian funding, blockchain has been used to address gaps in financial services outside of crisis zones. Project i2i provides a nontraditional solution for the unbanked population in the Philippines. While standing up the internet technology infrastructure necessary to establish traditional banking in rural areas is extremely challenging and resource intensive, with the blockchain, each bank only needs an iPad. With this, banks connect to the Ethereum network and users have access to a trustworthy and efficient system to process transactions. Though the system has successfully reduced the number of unbanked people in the Philippines, there are informed consent issues, as the majority of users have no other option and because of the data privacy rights.

While data privacy is a serious concern, blockchain also has the potential to support democracy and human rights work through data collection, verification, and even through supporting data privacy. The Chemonics’ 2018 Blockchain for Development Solutions Lab used blockchain to make the process of collecting and verifying the biodata of USAID professionals more efficient. The use of blockchain reduced incidents of error and fraud and provided increased data protection because of the natural defense against hacking that blockchains provide and because instead of sharing ID documents through email, the program utilized encrypted keys on Chemonics.

Truepic is a company that provides fact checking solutions. The company supports information integrity by storing accurate information about pictures that have been verified. Truepic combines camera technology, which records pertinent details of every photo, with blockchain storage to create a database of verified imagery that cannot be tampered with. This database can then be used to fact check manipulated images.

Civil.co was a journalism-supporting organization that harnessed the blockchain to permanently keep news articles online in the face of censorship. Civil’s usage of blockchain aimed to encourage community trust of the news. First, articles were published using the blockchain itself, meaning a user with sufficient technical skills could theoretically verify that the articles came from where they say they did. Civil also supported trust with two non-blockchain “technologies”: a “constitution” which all their newsrooms adopted and a ranking system through which their community of readers and journalists could vote up news and newsrooms they found trustworthy. Publishing on a peer-to-peer blockchain, gave their publishing additional resistance to censorship. Readers could also pay journalists for articles using Civil’s tokens. However, Civil struggled from the beginning to raise money, and its newsroom model failed to prove itself.

- New America keeps a Blockchain Impact Ledger with a database of blockchain projects and the people they serve.

- The 2019 report “Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies in the humanitarian sector” provides multiple examples of humanitarian use of DLTs, including for financial inclusion, land titling, donation transparency, fraud reduction, cross-border transfers, cash programming, grant management and organizational governance, among others.

- In “Blockchain: Can We Talk About Impact Yet?”, Shailee Adinolfi, John Burg and Tara Vassefi respond to a MERLTech blog post that not only failed to find successful applications of blockchain in international development, but was unable to identify companies willing to talk about the process. This article highlights three case studies of projects with discussion and links to project information and/or case studies.

- “Digital Currencies and Blockchain in the Social Sector,” David Lehr and Paul Lamb summarize work in international development leveraging blockchain for philanthropy, international development funding, remittances, identity, land rights, democracy and governance, and environmental protection.

- Consensys, a company building and investing in blockchain solutions, including some in the civil sector, summarizes (successful) use cases in “Real-World Blockchain Case Studies.”

References

Find below the works cited in this resource.

- Al Haque, Ali Abrar, Chakraborty, Narayan Ranjan, Chowdhury, Mohammad Jabed Morshed, Ferdous, Md Sadek, Nabil, Shirajus Salekin, & Pran, Md Sabbir Alam. (2022). Blockchain-based COVID vaccination registration and monitoring. Blockchain: Research and Applications 3:4

- Adinolfi, Shailee, Burg, Jon & Tara Vassefi. (2019). Blockchain: Can we talk about impact yet?

- Article 19. (2019). Blockchain and Freedom of Expression.

- Bacchi, Umberto. (2018). Scan on exit: can blockchain save Moldova’s children from traffickers?

- BBC News. (2019). Child abuse images hidden in crypto-currency blockchain.

- Bromwich, Jonah Engel. (2018). Alas, the Blockchain won’t save journalism after all. The New York Times.

- Cook, Bubba. (2018). Blockchain: Transforming the Seafood Supply Chain. WWF.

- Coppi, Giulio & Larissa Fast. (2019). Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technologies in the Humanitarian Sector. ODI.

- Corraya, Sumon. (2023). Bangladesh Election Commission rejects electronic voting. PIME Asia News.

- Dichter, Thomas. (2019). Blockchain for social impact? Be careful what you wish for.

- Finley, Klint. (2016). A $50 million hack just showed that the DAO was all too human. Wired.

- Hosein, Gus & Carly Nyst. (2013). Aiding Surveillance. Privacy International.

- (2018). Learning Review: Blockchain Open Loop Cash Transfer Pilot Project.

- Juskalian, Russ. (2018). Inside the Jordan refugee camp that runs on Blockchain. MIT Technology Review.

- Lehr, David & Paul Lamb. (2018). Digital Currencies and Blockchain in the Social Sector. Stanford Social Innovation Review.

- McCarthy, Niall. (2019). Bitcoin devours more electricity than Switzerland. Forbes.

- New America. Blockchain Impact Ledger.

- Price, Allison & Shang, Qiuyun. (2018). A Blockchain-Based Land Titling Project in the Republic of Georgia. Blockchain for Global Development II. (72-78).

- (2016). How blockchain technology could improve the tax system.

- Raghavan, Barath & Schneier, Bruce. (2021). Bitcoin’s Greatest Feature Is Also Its Existential Threat. Wired.

- UN OCHA. (2018). Blockchain for the Humanitarian Sector – Future Opportunities.

Additional Resources

- Blockchains and Cryptocurrencies: Burn It with Fire: a well-informed, critical look at blockchain technologies through a lecture and summary by Nicholas Weaver, Ph.D.

- Burg, John, Murphy, Christine & Jean Paul Pétraud. (2018). Blockchain for International Development: Using a Learning Agenda to Address Knowledge Gaps. MERL Tech DC 2018: a review of 43 blockchain projects in international development.

- Burg, John. (2018). Blockchain will impact your life…here’s how and what you can do about it. Medium: provides an optimistic path and some current case studies for future blockchain developments.

- Coinbase: an online digital currency wallet and trading platform offers educational material and a portal to learn and earn different emerging currencies.

- Digiconomist Sustainability Charts: provides updated charts on digital currencies, focusing on sustainability and environmental impacts.

- Finck, Michèle. (2019). Blockchain and the General Data Protection Regulation: Can distributed ledgers be squared with European data protection law? European Parliamentary Research Service.

- Nelson, Paul. (2018). Primer on Blockchain: How to assess the relevance of distributed ledger technology to international development. USAID.

- Popper, Nathaniel. (2018). What is the Blockchain? Explaining the tech behind cryptocurrencies. The New York Times.

- Rauchs, Michel et al. (2018). Distributed Ledger Technology Systems: A Conceptual Framework. University of Cambridge Judge Business School.

- The International Bill of Human Rights (consisting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights): should be reflected in laws and policy regulating blockchain-based technology.

- Tillemann, Tomicah et al. (2020). Virtual Currency Donations: Navigating Philanthropy’s New Frontier. Blockchain Trust Accelerator and International Center for Not-for-Profit Law.

- (2020). Digital Strategy 2020-2024.

- Wilson, Steve. (2017). How it works: Blockchain explained in 500 words. ZDNet: a short overview of the technology, focused on digital currencies.

- Yaga, Dylan J. (2018). NIST Blockchain Technology Overview. NIST: a balanced overview of blockchain technology, including a decision-making flowchart.